FOOTNOTES #25

CHAPTER 24 : THE BLASTING CONCEPT : Progressive Punk from SST Records to Mission of Burma

(absent for reasons honestly hard to fathom from the US edition)

PAGE 456

>Black Flag

The black flag is the traditional symbol of anarchism, but it would be fair to say that Black Flag were apolitical apart from a pure gut-instinct aversion to authority of all kinds, that cleaved if anything to the libertarian-capitalist.

Black Flag is also an American incesticide brand.

>Black Flag... Modern blues

Ginn also said Black Flag's music WAS equivalent to the barking of a dog in the dark, in fear and anguish.

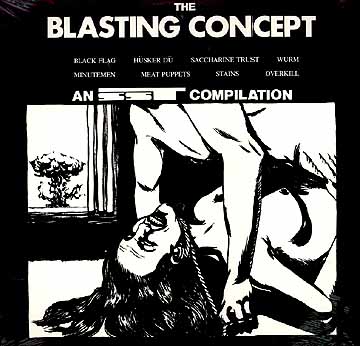

Blasting Concept album sleeve

PAGE 461

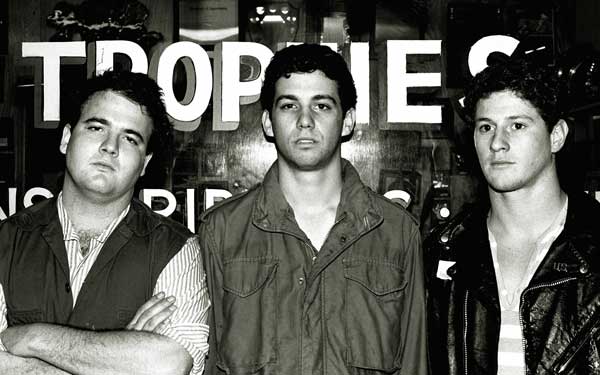

>"Boon saw things in terms of economy… very generous of him"

Mike Watt: “And it was also part of The Minutemen ideal of making things equal--if you’re going to talk about these things in terms of political economy, why not exemplify them with your band?”

the Minutemen

>George Hurley

Mike Watt: “George was hugely into Keith Moon. And also Bruce Smith--more than anyone I know, George loved those Pop Group records”.

PAGE 462

>Minutemen… right wing terrorists.. . internal enemies

More info here

Some extracts:

Convinced that the United States was under threat of an imminent communist

takeover, Robert DePugh, a disenchanted member of the John Birch Society,

founded the Minutemen in the early sixties. Forged as a "last line of

defense against communism," DePugh's secret warriors were dedicated to

building an underground army to fight against "the enemy within." 71

However absurd this paranoia may appear on the surface, it had serious and

deadly consequences for anyone caught in the cross-hairs. Before their

undoing in 1969, the result not of a sinister plot by "communist

infiltrators in the government," but because DePugh and others were

prepared to rob banks to finance the organization, the Minutemen had built

a formidable national network, with thousands of members stockpiling

secret arsenals with more than enough firepower to match their feverish

rhetoric. In 1966, 19 New York Minutemen were arrested and accused of

plotting to bomb three summer camps allegedly used by "Communist, left

wing and liberal" groups "for indoctrination purposes." Subsequent raids

uncovered a huge arms cache that included military assault rifles, bombs,

mortars, machine guns, grenade launchers and a bazooka.

In February 1970, six Minutemen from four states led by Jerry Lynn Davis

held a clandestine summit in northern Arizona. Surveying the ruins, they

were convinced that "communist elements" in the Justice Department had

destroyed the group. Undeterred by recent events, they formed the nucleus

of the Secret Army Organization (SAO).

As conceived by Davis and the others, the SAO would be armed but low-key:

a propaganda group with a potential for waging guerrilla war against

leftists, should the need arise. Emphasizing regional autonomy and a

decentralized structure, they believed they had inoculated themselves

against unwanted attention from "communist-controlled" government

agencies. Shortly after the meeting, chapters were established in San

Diego, Las Vegas, Phoenix and Seattle with promising contacts made in

Portland, El Paso, Los Angeles and Oklahoma.

History was a huge obsession for both D. Boon and Watts. The bassist recalls “being on tour and pulling into libraries to settle arguments.”

PAGE 466

>Flip your wig impulse checked by … tension and rigour

Roger Miller’s solution to this split sensibility was things like his “indirect solos” on songs like “Weatherbox” and “Fun World”, which managed to combine Gang of Four-like methodology with the orgiastic spirit of his axe-heroes Syd Barrett and Jimi Hendrix.

Mission of Burma

>Martin Swope

Roger Miller: "Martin would record a fragment of my guitar lick and bring it back later at a higher speed"

>Hear new melodies in there

This Rorsach-like invitation to hallucinate imaginary harmonies was another thing Mission of Burma shared with Husker Du.

PAGE 468

>tasty fuckin' lickmeisters

Even more of a fusion head than his brother, Cris Kirkwood also had a soft spot for the uber-virtuosos of “Euro-Rock”: a forbiddingly complex sub-genre of prog invented by Henry Cow (also known as RIO or Rock In Opposition).

PAGE 469

>the LAFMS-associated band Monitor… Carducci

Carducci had put a Monitor single out on his Thermidor label

>100 Flowers... Happy Squid

PAGE 471

>Neil Young

According to Derrick Bostrom, the country element on the album came more from Young than directly from the likes of George Jones

>>embarrassing secret.. Rockman… Tom Scholz

No diss intended to Boston, who built “More Than A Feeling,” the Sistine Chapel of Seventies pop-metal, a song I'll adore until the day I die

LINKS

Meat Puppets site maintained by drummer Derrick Bostrom with quite a lot of early interviews from Flipside and NO and such like in the "Words" section, as well as photos,etc etc

Joe Carducci online memoir of his SST days

Joe Carducci's insider's view of the making of Meat Puppets II

My Artforum review of Carducci's Rock and the Pop Narcotic, plus my profile of Carducci for The Wire

FURTHER READING

Me On Husker Du's Candle Apple Grey, their first album leaving SST.

Husker Du

Candy Apple Grey (WEA)

Melody Maker, 22 March 1986

By Simon Reynolds

Listening to this vast, volatile music, swept up in its power and space, I suddenly realised that these attributes are the precise opposite of the experiences Husker Du actually sing about — the lived reality of inertia, claustrophobia, isolation. The paradox of transfiguration — Husker Du's music wrenches numbness into fury and exultation. Only the Smiths make an equivalent alchemy of the grey areas of existence.

The Byrds' harmonies, the desolate purity of Hart and Mould's voices, a discreet trippiness, these are further clues. Husker Du (like the Smiths) use traces of folk, a roots music, to write songs about rootlessness. Both groups look to the ‘60s only to reinvoke what's most positive about the time — doubt about the costs of living a normal life, yearning for an indefinable more.

Husker Du's music trembles with all the nameless longings that ache beneath the skin. Sometimes they remind me of the Jimi Hendrix Experience — another power trio of virtuoso ability who created a rock noise that was spiritual. And I wonder if Husker Du's 'Somewhere' was our lost 'I Don't Live Today'.

But Husker Du have an ascetic quality that contrasts with Hendrix's febrile sensuality — their music rises above the body, refuses to solicit it (says 'don't dance, flip your wig'). Their love songs are chaste devotionals, almost hymnal. Husker Du approach the world, and their loves, with a mixture of pained bewilderment and awe. Their flight from the flesh is the only response to pop's soulless, sweaty sextravaganza.

I think also of another ‘60s-obsessed group. Where the Jesus And Mary Chain make pop fresh again by juxtaposing its sweetness with noise, Husker Du turn pop into noise — flaying these songs into a haze, smudging voice into guitar.

The feared corporate bland-out has not happened. There's a touch more clarity, a few more ballads. But this was coming anyway — Husker Du had taken velocity and noise as far as they could. The only way forward for them is to become gentler. Husker Du's achievement is a musical violence untainted with machismo: a violence that, paradoxically, heals. All they've done is to bring out more clearly the grace and compassion that always did rage at the heart of their ravaged sound.

Besides, these soft songs are the cruellest. No music mangles my heart so completely. The intimacy of "Hardly Getting Over It" almost destroys. 'Eiffel Tower High' features a sublime loop of melody that will crush the breath out of you.

There's never been anything cultish or difficult about Husker Du — please don't deny yourself this beauty any longer. For I don't know how much longer it can last — already Husker Du repeat themselves, musically and lyrically.

For the moment, though, I live for this pain.

Me interviewing Husker Du circa their second post-SST album, Warehouse: Songs and Stories

HUSKER DU

Melody Maker, 27 June 1987

By Simon Reynolds

In Atlanta, Georgia, The Replacements play me a tape of Husker Du’s live appearance on The Joan Rivers Show. It’s more than a little mind-blowing. The band unleash the great grey gust that is ‘Could You Be The One’, then troop over for a ‘chat’ with the lady herself.

It’s one of the most embarrassing pieces of television I’ve ever seen. Rivers is clearly terrified of the band, doesn’t know how to place or approach them, stammers out something to the effect that they used to be kind of radical and underground, but now aren’t quite so radical and underground, isn’t that so?

What’s unnerving her is that the band aren’t selling themselves on any level, either as outrage or as light entertainment, aren’t making anything of this opportunity to project themselves. They’re polite, awkward, somehow not-there. It’s not so much that they’re deliberately aloof as that they’re irretrievably apart. Rivers asks a question and I think she’s saying: "Which one of you is the wild member of the group and which is the commie one?" — turns out she said "calming". Then they traipse off again, to play ‘She’s A Woman’, having left an irreparable crease in the sleek fabric of the show.

It made me wonder whether a group like Husker Du can interact with this thing pop. The Smiths, at least, make a drama of their exile — their anti-glamour can be consumed as glamour.

But Husker Du refuse to act up — the ‘outrage’ they perpetrated on Joan Rivers was of an altogether quieter, less ostentatious order — they didn’t play up to the role of Misfit, they just failed to connect, to communicate on Pop’s terms at all — an eloquent incoherence. How, then, do they cope with things like videos?

Grant Hart: "The videos are of straight performances of the songs. Seeing as none of our songs are particularly etched in fantasy, they’re best portrayed naturalistically."

Like the other American thinking rock bands I’ve encountered (Throwing Muses and The Replacements) Husker Du loathe the exigencies of presentation and marketing, have a chronic fear of anything that suggests contrivance. American rock has never seen ‘image’ and ‘packaging’ as a means of expression in the way that much British rock has.

Perhaps this is because American daily life is more heavily saturated with showbiz glitz and advertising pizzazz than British life, and so it seems more urgent to escape the all-pervasive environment of kitsch, escape from the escapist, into the authentic, the ‘real’. Probably, it has a lot to do with the absence in America of the artschool/artrock interface that’s has been so hugely important in British pop history.

Either way, American rock (outside New York) has no notion of glamour as something you can radicalise: Throwing Muses will turn up for photo sessions in their tattiest, most everyday clothes, The Replacements will refuse to throw shapes for the camera and Husker Du will resist anything in the way of video presentation that’s redolent of advertising and its manipulation of the consumer.

Bob Mould: "The problem with videos is that, before they existed, you’d make up your own story, your own mental pictures, to go with a song. That’s what music’s for — attaching your own meanings to."

Somewhere along the way, pop ceased to be something that gave people a heightened sense of their own agency, and became something that programmed desires. What Husker Du hate above all is when things get fixed — they like to leave things open, in a flux. Maybe they’d get on better if they did give people one easy handle, if they weren’t so keen to leave things up to people’s imagination. Maybe the only way to get a hit is to work from the premise that most people’s imaginations are enfeebled, through under-use. As it is, they’re not even let near those kind of people.

Bob: "Our videos don’t get heavy rotation. Our records get played on college radio and on the progressive commercial radio stations. Whereas all the people in here [gestures at Billboard] get played several times a day on every radio station in America."

Ah, Billboard — whenever I look at magazines like Billboard or Music Week, it does my head in: I think of all the things that music means to me — dissension, speculation, complex pleasures, never-never dreams, the criss-cross currents of making sacred and sacrilege — and then look at how these people discuss pop — crossover between different radio sectors, aggressive marketing, instore promotion… who knows which kind of talk is more out of touch with the ‘reality’ of pop.

"Well, yes, it all depends on whether your conception of success is related to the outside world or to your own mind. With us, it ‘s the latter, so every song is a ‘hit’."

Quite. What is a ‘hit’ these days? Something that wreaks havoc in the private lives of a few people, or something that resounds widely and weakly across the surfaces of the globe? We’re back with DavidStubbs’ dichotomy between the small and significant and "huge insignificances" like Moyet or Curiosity. Two rival definitions of impact —purity of vision or breadth of effect.

All I know is that Husker Du hit me — this feels like the elusive ‘perfect pop’, the swoon and the surge. In one sense (sales) Husker Du are a ‘small’ band — in every other sense they are massive — in the scale and reach of their music, in the way they give a grandeur to mundane tribulations and quandaries — a musical equivalent of "the pathetic fallacy", (thunder and lightning as the dramatic externalisation of inner turmoil).

What is it about this ‘perfect pop’ that dooms it to be as distant from real Eighties Pop as the moon? That the music is too imposing, while the band, as individuals are too self-effacing, hiding behind the noise? That the music’s too violent, while the feelings that inspire it are too sensitive. That the songs deal with the loose ends of life but refuse to tie things up satisfactorily, instead confronting the listener again and again with the insoluble?

All these things distance Husker Du from today’s secular pop, with its twin poles of levity and sentimentality. But there are more material reasons why they don’t belong. The very fabric of their sound has no place in pop ’87, a blizzard that makes no appeal to the dancing body, but dances in the head.

Move in close and you see activity too furious for pop — flurry-hurry chords, febrile drumming — step back ten paces and you can take in the sweep and curve of the cloud shapes stirred up by the by the frenzy. Only AR Kane come close as sublime choreographers of harmonic haze. The stricken voices, the almost unbearable candour of their bewilderment and desolation, jar with Pop’s soul-derived universal voice of self-possession and narcissism.

‘Ice Cold Ice’, the fabulous new single off the Warehouse double, says it all — the chill of awe instead of the fire of passion, frost instead of flesh, the ghost of folk instead of the residue of R&B. Pop ’87’s aerobic humanism can’t take on this kind of enchantment.

But what do they think is the most unique thing they offer?

Grant: "The outlook, I guess… we’re creating music for human beings, not pop idols."

Bob: "I don’t see many people trying to be as honest as we are… I think the lyrics are enlightening without being too philosophical… I don’t think you associate a clothing style or a lifestyle with what we do… in that sense we’re not exclusive to anyone, we don’t exclude."

Do you agree that part of the appeal of being a band is the chance to prolong adolescence, to leave things open a little longer, to avoid the closures of adulthood?

Grant: "Well, there’s growing up and there’s growing boring, and the two are not necessarily inseparable. Generally, though, as a person gets established in their life, and the things that surround them are theirs rather than their parents’, they start to settle down. I see friends that are worrying about their bank overdrafts — all the things I worry about too, but not to the exclusion of everything else. And the next step is that you start playing the game, kissing up to the boss, all to ensure the security you’re afraid to lose. But what you do lose is the ability to live for the moment, because life gets so bound up with planning and providence. People get conservative as they look to preserving their life investment."

One of the first things to go when this settling down sets in, is music, or at least rock of the Husker Du ilk. People cease to be able to take on such music. It’s too demanding — literally, in terms of investment of energy and attention; but also in the sense that rock is like a reproach, can get to be an unwelcome nagging reminder of dreams that have been foregone. It becomes unbearable to listen to music, after a while.

Bob: "Well, almost everyone does give up music, sooner or later — it’s a matter of when…"

Grant: "But there are those who give everything up all the time and right from the start. So even to hold out for a while is not so bad."

Who do they feel are their kindred spirits in rock?

Bob: "Who’s at Number 186 in the Billboard Chart this week, ha ha ha ha! No, there are some like-minded groups about, groups that have abandoned the idea of pop stardom — we’ve even been accused of triggering that off… bands like R.E.M., Meat Puppets, Black Flag… bands who can be widely successful in their own minds because of the psychic rewards of what they do. A band like R.E.M. that has a very internally run programme — they’ve got a manager that’s been with them since day one, they’re very homebase-oriented, having refused to move to New York or L.A. Similarly, we decided to stay in Minneapolis right from the start. Now things are turned around so that a friend of a friend knows a musician who moved from Hollywood to Minneapolis, in order to be discovered!

"I like the fact that we’re self-sufficient, that we look after our own finances, that we don’t have a set regimen dictated by a corporation or anybody. One of the results of the life we lead is that we don’t divide work and play. When I’m not working on music or doing specific administrative tasks, I’m writing or reading or drawing, but all these things have an input into the music."

How do you want people to be affected by the music?

Grant: "This may sound a little overwhelming, but I’d like them to come out a better person than when they came in, as a result of an effort by both audience and the performers. We’re appreciated by a different enough range of people — rednecks, hippies, punks, 50-year-old jazz buffs — that I personally am really satisfied that there’s so much love going down. I’m also proud of the price we take in what we do… I wish they made drums like that!"

Is there a kind of politics in Husker Du, in that you deal with the discrepancy between the promise of America and most people’s lived reality of deadlock and impasse?

"There’s politics in the sense of people trying to gain control of their own destiny. Life is too short to worry about who’s on top at any given time — politics is like advertising, the basic products beneath the different wrappers are much the same — it’s more important to avoid being stepped on, to find a life that doesn’t involve a giant foot hovering over your head perpetually. The golden rule is: be neither a foot over someone’s head, nor a head under someone’s foot."

And are there ‘spiritual’ concerns, too?

Bob: "I’m a questioning person. I’d like to find out why certain things are the way they are and, if that’s spiritual, then I’m a spiritual person. Things like time interest me. I overheard a guy on the airplane saying that the Japanese are 25 years ahead of us. Now which 25 years did he mean — 1780 to 1805, or 1962 to 1987? How do you qualify time? Is time the same for a guy aged 25 who’s never eaten meat and for a guy of the same age who’s taken speed for the last 10 years…"

Grant: "In hamburgers!"

Bob: "A good question is so much better than a bad answer. If you had all the answers, why go on? There goes all your spirit, your reason for living."

Me on Meat Puppets live in 1987

MEAT PUPPETS

Hammersmith Clarendon, London

Melody Maker 1987

by Simon Reynolds

The first ever UK appearance by the Meat Puppets finally gave me a glimpse at just who exactly it is that's been keeping the faith for so long. It's a motely, peculiar congregation assembled tonight--skatepunks in baseball caps; snakebite-quaffing tradpunks; cardigan-and-one-earring herbivore anarchists like the nice, caring bloke in EastEnders; bearded, more-or-less unreconstructed hippies; bespectacled nerds of the Albini/Santiago stripe; REM drummer lookalikes. And rock critics, of course. This heterogeneity reflects the schizo-eclectic nature of Meat Puppets music, suggests that each strand of their following trips on a different facet of the group--the acceleration; the virtuosity; the desolation and vulnerability; the free noise wig-out.

Over seven years and five albums, the Meat Puppets have created for themselves four distinct sounds, each one a perfect amalgam of country, free jazz, funk and acid rock, an alloy rather than a cocktail. Each of these sounds has been completely new, completely theirs.

Tonight, at first, it felt like something was missing. The mellower songs from Mirage don't led themselves to the straight slam approach, but this is what they got. The result--neither the billowing cobwebbed delicacy of vinyl, nor the mind-scattered total frenzy of live legend, but an inconsiderable bumptiousness, a speed-country tumult that was consistently impressive, but never left you agog. The audience brimmed o'er anyways, such were the pent-up expectations; Curt and Kris Kirkwood flipped their wigs (Kris's a tange of orange tortelloni, Curt's a Ma Bates mop)… but something was missing.

And then suddenly the air was sown with magic; there was an abrupt and unaccountable shift from merely "playing good" to "playing possessed", a sudden, seemingly arbitrary willingness to stretch the borders of the songs, cast loose their mooring in the downhome. Songs like "Out My Way" and "Up on the Sun" --frenetic speedfunk, a manic, flashing secateurs snip'n'clip--hurtle like rocket cars across mud-flats, then careen into prolonged and exhaustive supernovae whose final reverberations seem to take centuries to dissipate. Then there's the brutal plangency of "Hot Pink"--light so intense it's turned solid, a crystal canyon over whose jagged edges your synapses are dragged. "Love Our Children" is rendered straight, then strays into an echoplex meander (although that words suggests listlessness, not a foray this purposeful and driven); the three chord ending is impossibly elaborated, each chord becoming a Niagara of phosphorescent improvisation; the final note dilates into a giant dewdrop the size of a small universe. Finally, it's as though the members of the audience are just motes swirling up the cyclone spout of the Meat Puppets' halcyon chaos.

The Meat Puppets's MOST visionary moments have a blinding brilliance--but that's the definition of "vision": something that interferes with regular, regulated perception, ensures you will never see the world in the same light again.

Me on a Meat Puppets anthology

MEAT PUPPETS

No Strings Attached

SST

Melody Maker, January 19th 1991

By Simon Reynolds

One of the last decade's best kept secrets, Meat Puppets were/are a trio of sunstruck visionaries from Phoenix, Arizona. Meat Puppets fell through the cracks that demarcated Eighties music: they didn't fit anywhere because they fitted too much into their sound. This compilation documents a decade of "forever changes".

With the debut EP In A Car and LP Meat Puppets 1, it's like peyote has gotten into the water table and spawned a lost tribe of brain-baked bumpkins with their own mutant band of acid-C&W-hardcore-jazz-fission. "Reward" is a Niagara of raving, electrified virtuosity. Their cover of "Tumblin' Tumbleweeds" is even more unraveled, the guitar as eerie as wind whistling through telegraph wires.

By Meat Puppets II, singer Curt Kirwood had ditched the foaming-at-the-mouth delivery in favour of a frayed country croon, while his guitar-picking shifted from freak-out to a hillbilly Tom Verlaine. Meat Puppets were now clearly "all about" the derangement induced by prolonged exposure to the unrelenting glare and denuded, undifferentiated dunescape of the Arizona desert: a state of grace caught in the line, "I can't see/the end of me/My own expanse/I cannot see". "Lake of Fire" is a shaman's blues after forty daze in the wilderness. "Split Myself in Two" maelstroms along like a tornado-in-reverse, a sandstorm flickering with fleeting, phantasmic, sculpted shapes that suddenly blossom into quicksilver peals worthy of Marquee Moon. And this was back when the only people playing acid rock were Husker Du.

By '85's Up On the Sun, Meat Puppets had added funk to their febrile fusion. Some folks reckon they got within spitting distance of Grateful Dead at this point, but I wouldn't know shit about that. But the title track exemplifies the brutal plangency of their sound: light so intense it's jagged, scraping all the encrusted grot off your senses. At its uttermost, this LP was as radical a rearrangement of rock syntax as "Eight Miles High". But just as this compilation ignores the peaks of the second LP ("We're Here", "Aurora Borealis", "Plateau"), so too it bypasses the high points of Up on the Sun ("Hot Pink", "Away", "Two Rivers") in favour of the more crowd-pleasing numbers: the gladfoot hurtle and rippling radiance of "Swimming Ground", the quirked-out speedfunk of "Buckethead".

Mirage, from 1987, auditioned a mellower, less expansive Meat Puppets, with one eye on the mainstream. But "Confusion Fog" reitereated their "bewilderment in the wilderness" mysticism. In an interview, Kirkwood told me that his visionary tendencies stemmed from a childhood bout of encephalitis; after awakening from the coma, he found that, "I daydream an awful lot. I don't need to take drugs".

After the dragonflies-in-your-stomach shimmer of Mirage, Meat Puppets went off the boil. Huevos saw them regressing to their teen apprenticeship in boogie bands--all done with exquisite inventiveness, but square-sounding after the solar flair of yore. And last year's Attacked By Monsters was even more metallic, albeit ferociously fluent and dazzlingly nuanced. But one track, "Like Being Alive", was a return to form, the slower pace allowing Kirwood to roam, billow, soar to Hendrix-ian heights.

"To flirt openly with vapour… making love to open windows." At their outermost, Meat Puppets were the pure distillation of the mystically intangible, awe-struck side that some of us liked in R.E.M. . At their peak, they were "heads" adrift without a counter culture to argue their case. But even now Meat Puppets' loss-of-self could be your gain.

Me on SST's Blasting Concept 2 album of 1986 and other past-its-prime SST releases

VARIOUS ARTISTS

Hardcore Albums

Various labels

Melody Maker, autumn 1986

By Simon Reynolds

Like British punk, hardcore went awry when it began to worry about 'progressoin', when doubt crept in about the music's very strengths of economy/discipline/aggression. Those limIts were the source of the music's power, and the attempts to explode those limits only led to the return of the hippy things--"self-expression", "growth", fusion, conceptualism, muso-ship. Take Black Flag, who began with the most economical of existensial stances--"my mind's a mess/my body's a cage"--and rattled the bars. Now their abysmally prolific output includes LPs of instrumentals, spoken word albums and books.

Blasting Concept 2 conveniently invites comparisoin with its predecessor. The tracks on the earlier SST sampler were like bolts of lightning through tired flesh; the new tracks, often by the same bands as before, suck me into their inertia. Most of this music is poor Black Sabbath, all slow tempos and migraine-morose, with pure H/M titles like "Mystery Girl" and "Death Ride". Only Meat Puppets' offering squirms out of this sonic straitjacket.

Greg Ginn, Black Flag's guitarist, has put together a 'supergroup' (!) called GONE, and they're equally hung-up on the stop-start riffs and tempo twists of "War Pigs". Let's Get Good and Gone (SST), an instrumental LP, is perhaps the feeblest failed virtuosity, the deadest doodling I've ever suffered. The bassist strives to be Bootsy Collins but most of these tracks sound like the drawn-out death throes of a wounded animal.

Black Flag's Chuck Dukowsi crops up in SWA, whose Sex Doctor (SST) is straight metal only marginally uglier than Graham Bonnet. SACCHARINE TRUST, meanwhile, have "developed" from the taut vicious punk of their Blasting Concept I track to a kind of… jazz-rock, all stunted improvisation and hippyish haiku-mystical "poetry". They recently released a live LP of spontaneous improvisation but their studio newie We Became Snakes might just as well have been made-up on the spot, too.

ZOOGZ RIFT's inspiration extends to the title of his album, Island of Living Puke (SST) but can't match the scope of his ambition to sound like Zappa, the Residents, Art Ensemble of Chicago… A farrago of mixing-desk mucking-about and puerile waaaaacky humour.

But stasis's diminishing returns are no alternative to "progression" either. DIE KREUZEN weigh quaintly in with October File (Touch and Go), efficient hoarse spite, while NO ALLEGIANCE's Mad (Destiny) has burly riffs and a bleary, retched venom almost worthy of commendation.

With a few exceptions, like Scream or The Descendents, American hardcore seems to be either staid or a sorry sprawl of indulgence these days.

All non-pictorial contents copyright Simon Reynolds unless otherwise indicated

No comments:

Post a Comment